I’ve often said that these goofy “Bike Law” issues which take up just about my entire law practice will not be litigated through traffic tickets in traffic court but in cases of severe injury or death, because that’s where the money is… on both sides… the victim is seeking big damages, and the defense team is well-funded by insurance companies and hyper-analyzing the law to find ways to pick apart [some might say screw over] the cyclist’s claim…

I found a very interesting case today in a unique manner. A client sent me a link to a

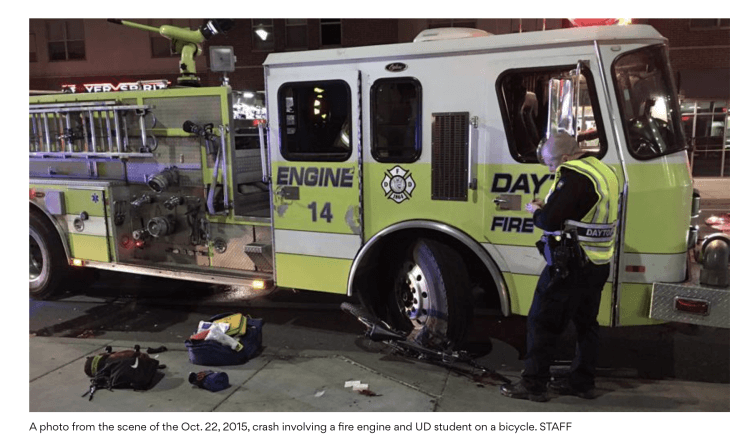

news report from Dayton, Ohio. The City is paying $150,000.00 to a cyclist who was hit by a Dayton Fire Department vehicle. I thought… hmmm… that’s neat… and dug into it.

Turns out that the most interesting details in the case were buried in the court case records which I dug up on the Clerk’s website and have to do with the Ohio Constitution, ORC Sec. 4511.07, Home Rule and the power of cities to pass their own local bike laws…

A Constitutional Bike Case?? Who Knew???

The case is Kane v. City of Dayton. It’s a trial level decision, so the Court’s decision has no real precedent value but it’s the very first case I’ve found that discusses 4511.07, Home Rule, Bicycles and a conflict between state law and local law.Quinton Kane, the cyclist, was struck by a Dayton Fire Department truck. Crash happened about 30 minutes after sunset. Kane was riding in a bike lane but didn’t have a light on his bike.

Ohio’s State Traffic Law says a cyclist needs a light AT sunset [ORC Sec. 4511.56] … BUT… Dayton has a local ordinance that says a cyclists did not need a light operating on their bikes until ONE HOUR AFTER AFTER SUNSET… So Kane’s behavior [no light, 30 minutes after sunset] complied with local law but violated state law.

ORC Section 4511.07 was added to Ohio law in the Better Bicycling Bill of 2006. The law authorizes municipalities to create local ordinances that govern the operation of bicycles on local roads. However, the law forbids laws that are “fundamentally inconsistent” with state law. Here, the local ordinance is arguably kinder and gentler than state law – it allows cyclists to ride an hour longer without using their lights – but is definitely not “consistent with” state law.

The City filed a motion for summary judgment asking the court to find that the cyclist was negligent per se for violating state law. The cyclist filed a response relying, obviously, on city law.

The Court looked at it from a Home Rule perspective and said:

– Under Ohio Constitution, Art XVIII, Sec 3, Ohio’s “Home Rule” Amendment, a city does not need 4511.07 to make its own laws. The City has authority within the Ohio Constitution to make its own laws and that authority cannot by limited by a statute passed by the state legislature. A city’s Constitutional powers trump the legislature’s attempts to try to control the city. The Court ruled that any local laws in conflict with state law must be evaluated under the Home Rule analysis set forth by the Ohio Supreme Court, not 4511.07’s “fundamentally inconsistent” test.

The Court then analyzed the Dayton rule using Home Rule analysis from Marich v. Bob Bennett Constr. Co (2007), 116 Ohio St.3d 553 and:

– found the Dayton Ordinance to be “in conflict” with state law

– found it to be an exercise of “police power” which must yield to state law ->4511.56

– Found ORC 4511.56 to be a “general law” [meeting the 4 part test for this] in that:

– It is statewide & comprehensive

– It applies to all parts of the state and operates uniformly throughout

– It sets forth a “police regulation”

– It prescribes a rule of conduct upon citizens generally

Based on this analysis the Court found 4511.56 to be a general law… “Therefore,” the Dayton ordinance “must yield to” ORC 4511.56 as “…it is settled law that ‘where a legislative enactment imposes upon any person a specific duty for the protection of others’ the failure to perform that duty is negligence per se.”

So, the court held that the cyclist was negligent per se in not having a light operating after sunset… but… that does NOT end the case.

In order to “win” an injury claim in Ohio the plaintiff must show that the defendant was negligent and that this negligent conduct was the “proximate cause” of the crash and plaintiff’s injuries. The court said that the fact that the plaintiff was negligent does NOT mean that his negligence, his failure to use a light, was the proximate cause fo the crash. Perhaps the area was so well lit that the plaintiff should have been seen. Perhaps the driver of the fire truck was so distracted that he wouldn’t have seen the plaintiff anyway. Perhaps other facts and circumstances needed to be evaluated by the jury to determine what the true “cause” of the cash was. The court ruled that issues of proximate cause and Dayton Fire Department’s negligence remain.

Ohio is a “comparative negligence” state – like most states. This means a both sides can be negligent, and the plaintiff can still “win.” Under Ohio law, if the cyclist was negligent, but that negligence didn’t really play a role in why the crash occurred [i.e., the lack of a light was not the “proximate cause” of the crash] then a jury when evaluating/comparing the negligence might find the city solely [100%] at fault. A jury might also award some level of negligence to each side. Under Ohio’s comparative negligence law the plaintiff still WINS the case if her/his level of negligence is 50% or less… but the damages awarded are cut by that percentage. So if the plaintiff wins $100,000.00 in damages but is found to be 25% negligent then the award is cut to $75,000. If the plaintiff is found to be 50% negligent the damages are cut by 50% in our example to $50,000.00

–> BUT… In Ohio, if the plaintiff is 50.1% negligent or higher the plaintiff wins ZERO… Across the Ohio River, in Kentucky, they have what’s called “pure” comparative negligence. This means a plaintiff could be 99% at fault but still win 1% of the damages awarded. North Carolina is one fo the last states to still use the old “Contributory Negligence” rule. This means that ANY level of negligence by the plaintiff causes the plaintiff to LOSE the case entirely. That was the rule generally when I came out of law school in 1982, but most states have abandoned that harsh rule in favor of some form of comparative negligence…

SO, after the Court in Dayton made it’s decision- plaintiff is negligent per se, but the case goes to the jury – the parties sat down in Mediation and resolved the case for $150,000.00. The plaintiff suffered severe injuries [the fire truck ended up sitting on his leg until it was moved off] so I’m sure $150,000 is a significant compromise but it still represents some excellent legal work.

4511.07 has been around since 2006, but this was the only case I’ve found that has analyzed a local statute on bicycling in this fashion. Since it was a trial court decision in a case that resolved, and was not appealed, it has no precedential value. It still gives us, as advocates and Bike Lawyers, some insight into how at least ONE court views the Home Rule issue vis-a-vis Ohio’s Bike Laws…

Good Luck & Good Riding!

Printed from: https://ohiobikelawyer.com/uncategorized/2019/01/constitutionalbikecase/ .

© 2024.

You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

RSS feed for comments on this post ,

TrackBack URI

Excellent analysis, Steve. You made the issues easy for non-lawyers to understand.

I’m looking at the news photo with your blog post and the collision appears to have been a right hook . That being the case, the presence or absence of a headlight on the bicycle would be relevant only if the cyclist was overtaking the fire truck. Ohio statutes do require a taillight but if the truck was overtaking the cyclist the question arises as to whether a rear reflector and/or pedal reflectors were in place and would have been sufficient to alert the driver to the bicyclist’s presence. Usually, they do if the motorist is overtaking; while a cyclist is wise to use a taillight, the statue requiring one may impose an unfair burden on the cyclist. The issues of fact in this case involve much more than the presence or absence of either a headlight or taillight, and the absence of either may not have been a proximate cause.

Yes John, that goes to the proximate cause argument. Plaintiff says “Sure I was negligent but my actions didn’t make the crash happen. I was there to be seen by anyone who was looking.” The site photos filed by plaintiff along with his response to the MSJ were agreed to by the FD driver to be an accurate reflection of the conditions, and look pretty darn bright.

I had a case in which a cyclist had a headlight, but no taillight, and was rear-ended, and killed, before sunrise. I was able to make sufficient arguments to the insurer about the conspicuity of the rider that they paid a decent sum to the widow and children to make the case go away.